Creativity vs Depression

It might seem too simple a proposition, but could depression sometimes reflect a crowding out of "creative forces" joy and inspiration, at the hands of certain "forces of stress" like fear

and anger?

Interestingly, some of the most respected current perspectives on depression put significant emphasis on creativity.

Among these perspectives are positive psychology; play as protective of mental health; locus of control; the humanistic perspective.

Positive Psychology

Martin Seligman, Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, cautioned against focusing exclusively on what can go wrong with the human mind.

For a complete picture of mental health, Seligman draws our attention to a set of so-called “core virtues”.

Seligman’s book Character Strengths and Virtues

from 2004 includes the following as “core virtues”: creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, innovation, courage, integrity, zest, humanity, love, kindness, forgiveness, humility, self-control, and gratitude.

Not only is “creativity” singled out as a “core virtue” in its own right, it is central to all the others listed.

Each of the "core virtues" displays a cardinal feature of creativity, namely that they arise by themselves

- without need for prompting - and operate as a law unto themselves.

Collectively, these “core virtues” are what give energy to our innate initiative and enterprise.

They are what give us our “drive” when we’re not being controlled and compelled - and robbed of the space to think for ourselves

and be as we actually are

- i.e. true to our innate nature.

These “virtues” belong as essential "ingredients" to what Seligman calls “positive psychology”, where the emphasis is of the mind as a place not just of “disease”, but of health - and health that can go on improving.

For Seligman, the work of defeating depression belongs alongside the work of reflecting on - and establishing - healthy states of mind.

This recalls the seminal Alma-Ata Declaration of the World Health Organization, which highlighted the goal of promoting not merely the absence of disease or infirmity... [but] the attainment of the highest possible level of health.

Play as Protective of Mental Health

“The opposite of play is not work—the opposite of play is depression.” Brian Sutton-Smith.

Dr Stuart Brown, founder of the National Institute for Play

in the US, offers a similar view: “When play is denied over the long term, our mood darkens. We lose our sense of optimism and we become anhedonic, or incapable of feeling sustained pleasure.”

*

In his TED talk The decline of play, Peter Gray looks at the problem of denying the place of play in modern society - and sees how detrimental this can be to children.

Peter Gray notes a worrying pair of trends since the 1950s:

(1) A “continuous erosion in children’s freedom and opportunity to play freely”; and,

(2) A “well-documented increase in all sorts of mental disorders in childhood”... including

- a staggering 5-8 fold increase in major depression or clinically significant anxiety disorder among children

- a doubling of the suicide rate among young people aged 15 to 24

- a quadrupling of the suicide rate among children under 15

(3) “A decline of young people’s sense that they have control over their lives” - such that they have “more and more of a sense that their lives are controlled by fate, by circumstance, and by other people’s decisions.”

He points out that research shows that when young animals are denied the chance to play, they adopt a fear-first approach in later life, freezing in the corner and losing their usual preference to explore their environment.

At the same time, he points out the finding by anthropologists that within “hunter gatherer cultures, children and teens are free to play all day long”, and that anthropologists had observed “children in these cultures” to be “among the brightest, happiest, most cooperative, most well-adjusted and most resilient children that they had ever observed anywhere.”

Keeping Control: "Locus of Control"

Where we have a sense of having no control over our life - such that we feel that our life is outside of our control, as per point (3) above - we are described by psychologists as having an “external locus of control”. When this “external locus of control” applies, the research suggests, we are placed at greater risk of depression.

As such, the alternative - “internal locus of control” - where we identify ourselves as playing a central part in shaping our own “destiny” - is surely something essential to encourage when protecting ourselves against illnesses like depression.

There's a clear link, here, with the work of Deci and Ryan - who have demonstrated the health and well-being benefits of maintaining our own, innate - autonomous - motivation.

It also calls to mind the Whitehall Studies that tracked the health of thousands of British civil servants. These looked at the workplace stressor of lack of control over one’s job, and found that among those studied, exposure to either of these increased their risk of coronary heart disease by a full 70%.

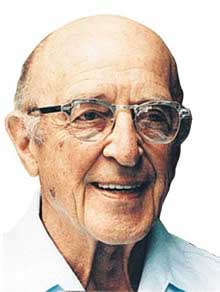

Carl Rogers and the Humanistic Perspective

Carl Rogers (1902 - 1987) was a refreshing antidote to the “one size fits all”, “expert knows best” approach to the “correcting” of emotional disorder. For Rogers, our personal potential is fulfilled - and our true direction is recovered - only when we trust our own self.

The school of psychology that he helped found, humanistic psychology, proposes that at its heart, our human nature can be trusted - our own not least.

Here’s Rogers’ basic proposal: work with one’s own self, and it will reward us with immense intelligence.

For Rogers, we human beings come equipped with our own means of:

- discovering truth, through our own, direct experience

- putting a knowledge of that truth to good use (including insightful self-knowledge)

*

Holding a real respect for the human’s being’s innate resourcefulness, Carl Rogers devised a whole new approach to therapy.

Just as Socrates used to see himself as the “midwife” to the birth of another’s insight, Rogers as therapist stepped out of the customary expert role, and focused on creating a supportive environment for clients - in which they could safely recover confidence in their own self.

Being not judging towards his clients, but providing them with what he called “unconditional positive regard” and empathy, Rogers effectively modelled the same generous spirit that he hoped to encourage in them... so that they, when appraising their own self, were equally forgiving and compassionate.

*

Now, just as during Rogers’ time, there is plenty of policing of what we think, say and do.

Compared with the 1950s, we can make the case that there’s a greater freedom to dress however we want to. Yet standards have never gone out of fashion. The “shoulds” and “oughts” that oblige us to comply with set definitions for “good” and “virtuous” person might have shifted, but they have not gone away.

When we make comparisons between ourselves and the rich, glamorous and famous - as we are apt to do more and more in an age of social media - there’s not necessarily any conscious decision we make to opt in. Rather, such comparisons can just work away at (unconsciously) undermining our self-esteem, whether we really want that or not.

In the meantime, the use of personal “enhancements” - cosmetic procedures, for example, or designer clothes - might start out as something we remain in control of, but might slowly turn into a compulsion. These might, ultimately, leave us feeling more and more dissatisfied with our appearance/ popularity etc.

.

Framing this dilemma in the language of Rogers, we would say that we’re making the mistake of identifying too strongly with an ideal

self - a pre-defined version of our self that we aspire to achieve.

The more unforgiving and bullying we are towards our real

- unadulterated - self, and the more desperate we become to achieve our ideal

self, with no expense spared, the more we become cut adrift from our real

self... and left in a state referred to by Rogers as “incongruence”, and so prone to deep unhappiness.

Rogers’ humanistic approach - and his cultivation of unconditional positive self-regard just as much as regard for others - offers us the chance to free us from standards, “shoulds” and “oughts” that have turned toxic, whether they are directed at us by controlling others, or spearheaded, perhaps, by guilt, shame or narcissism.

*